Yet another thought piece about LLMs. I know. Bear with me.

This is an attempt to put words around something I think most developers are experiencing right now but haven't had time to make sense of. Programming with LLMs is genuinely useful and genuinely destabilizing. These two things coexist. If we pretend the second one isn't happening, we will all burn out.

At Pydantic, we build tools that developers use to validate data, build AI agents, and observe what their systems are doing in production. We are, quite literally, in the business of making LLM-powered software more reliable. And we are also having a weird time.

This isn't a thinkpiece about whether AI will replace programmers. It's not a doomer essay and it's not a hype piece. It's an honest account of what it feels like to be a developer right now, from someone inside it, and some thoughts on what might actually help.

Hands in the fabric

When I was first learning to code in my early twenties, I remember having this distinct sensation that programming let me dip my hands into the fabric of the universe and shape it to my will. This was, of course, before I'd hit too many compile errors. But that feeling of touching some deep fundamental layer of abstraction, of being able to make things from nothing but logic, has always stuck with me.

I'm not a Computer Science graduate. I'm a designer and a programmer — formally trained in the first, self-taught in the second. I came to the formalisms of software engineering through painful experience rather than academic instruction. If anything, that made me take those principles more seriously once I understood them. When you've earned your opinions about architecture and code quality the hard way, they feel less like textbook rules and more like scar tissue.

That primal feeling of creation? It's the same promise that the low-code and no-code tools of the 2010s kept making but never quite delivered on. I'm old enough to remember building web pages in Dreamweaver, watching Adobe spruik zero-code design tools that generated absolute spaghetti under the hood. It was always almost there, just good enough to hint at a future that was just around the corner (if only you were smart enough to grasp it).

If you're cynical about the current wave of AI tools, I get it. We've been promised this before. But this time the gap between promise and reality has actually, finally, narrowed to something meaningful. And that's exactly what makes it so unsettling.

What "the code writes itself" actually feels like

Yes the code (sorta) writes itself, but the human reviewing, directing, and course-correcting feels worse, not better.

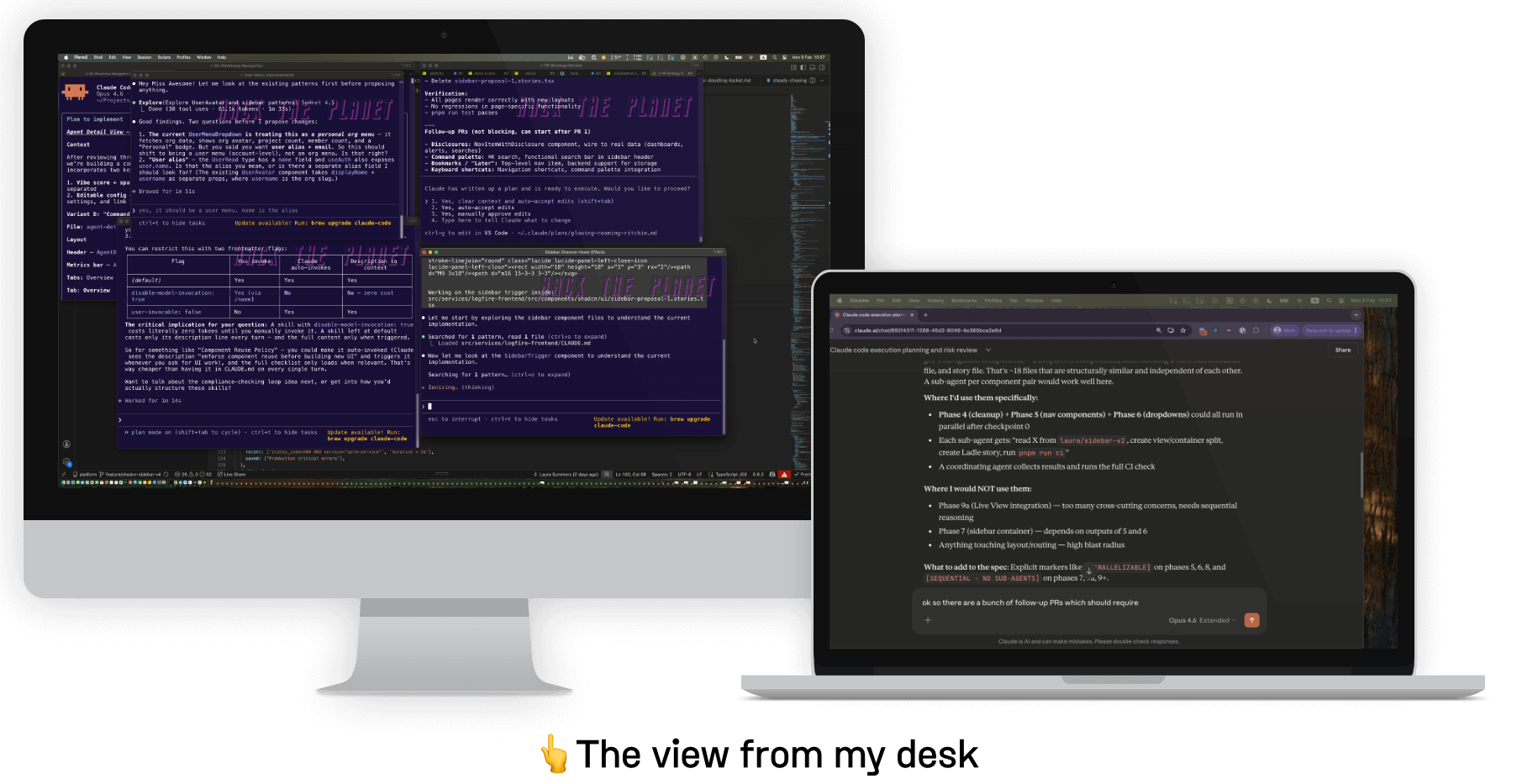

I recently had a conversation with my colleague Douwe, who maintains the Pydantic AI framework and has been one of the most thoughtful people I know about integrating LLMs into open source workflows. He described waking up to thirty PRs every morning, each one pulled overnight by someone's AI, and needing to make snap judgment calls on every single one. The temptation to delegate the review itself to an AI was enormous. But, as he put it: "at that point, what am I still doing here?".

The honest truth is that in the last few months, there have been days when I have spent close to two full days writing a plan for an LLM to execute: obsessively clarifying, specifying, re-specifying, only to have it still do something inexplicably stupid. Port a React hook into a Storybook story file. Read from the wrong plan. Invent components that don't exist. And these aren't errors of capability; they're errors of coherence. The models are smart enough to produce plausible code, but not always smart enough to maintain a coherent intent across a complex change.

This creates a peculiar new kind of fatigue, the fatigue of supervision: of holding the intent in your head while the machine generates volumes of mostly-correct output that still needs your eyes, your judgment, and your taste. Douwe put it well: he used to get a dopamine hit from collaborating with a real person on a cool feature in open source. Helping someone become better at their craft. Now, he said, "everything I write goes into some AI black hole. There's no person on the other side actually learning anything." That loss is real and it's worth naming.

The intensity trap

Simon Willison recently highlighted a Berkeley Haas study which describes how AI usage increases the intensity of work. The constant pull of "one more prompt at the end of the day, one more feature that could make this perfect." I felt that one in my bones. I was up until nearly 2am recently, prompting, because I was so close to getting a plan right. Or so I thought.

Marcelo, another Pydantic colleague, when asked about his Claude Code session freezing said: "just open 5 claude sessions. You'll never notice because you're busy giving feedback to the others." He was joking. I think. But it captures something true about the current moment. The parallelism is exhilarating and kind of feral. The number of things you can start has dramatically increased. The number of things you can thoughtfully finish hasn't changed at all, because that part still requires the one resource we can't parallelise: your brain.

Here's a term for what I think is happening: the human reward function problem. In machine learning, a reward function tells an agent what good looks like. Writing code by hand was never easy, but it was full of small rewards. Solving a problem in your head. Understanding a gnarly bit of logic. Watching the code compile. The feeling of control. LLM-assisted programming has automated much of the work that generated those dopamine hits and replaced it with the cognitive load of review and supervision. The satisfying part shrank. The exhausting part grew. And there are no new rewards to fill the gap.

If you're feeling like your work is simultaneously more productive and less satisfying, you're not broken. The feedback loop is broken. And I think we need to start treating that as an engineering problem in its own right, not a personal failure.

It's also, frankly, quite lonely. Programming with an LLM is an intensely solitary activity.

You and the machine, going back and forth, refining and prompting and reviewing. The natural moments where you'd turn to a colleague to ask a question, to rubber-duck a problem, to share the small victory of something finally clicking. Those moments get quietly replaced by another prompt. In a team without a strong existing culture of collaboration, this has a tendency to further separate people, to chill communication at precisely the moment when you most need the reassurance that other humans are finding this hard too.

And it's addictive in a way that makes the isolation worse. Sometimes you get something brilliant, sometimes garbage, and you never quite know which. Textbook Skinner Box. It can be genuinely hard to step back and remember that you're allowed to just... write code. But switching between LLM-assisted and manual work is jarring and uncomfortable, two very different modes of thinking, and it takes a kind of maturity and confidence to give yourself permission to switch.

Breakpoints

This moment brings to mind the fear and angst caused by responsive design. I was working as a designer and frontend developer at the time, following Ethan Marcotte and the Zeldman / A Book Apart crowd like everyone else, and I remember how unsettling it felt to be told that the fixed-width layouts we'd all mastered were basically over.

For the younger devs: there was a genuine cultural moment around 2009 when websites moved from fixed, pixel-perfect, magazine-style layouts to fluid, responsive ones. And designers hated it. The loss of control was existential for people whose entire identity was built around precise layouts and perfect grids. You're telling me the user might see my design at any width? On any device? That the layout I crafted would... flow?

Image design by Jyotika Sofia Lindqvist

The resistance was intense. And it was understandable. People had built real expertise in a paradigm that was being fundamentally disrupted. The designers who thrived through that transition were the ones who reframed their skills. The eye for proportion still mattered. The understanding of hierarchy still mattered. The craft didn't die, it evolved. What became less relevant was the obsession with pixel-level control. What became more relevant was understanding systems, adaptability, and designing for uncertainty.

I don't want to oversell this parallel. Responsive design played out over years. The current shift is measured in months. Agencies lost clients and designers lost gigs over the responsive transition, but it didn't carry the same existential dread. The stakes are materially different, and the pace is genuinely exhausting in a way that the responsive transition never was. But the underlying pattern, of craft evolving rather than dying, of the core skills mattering more not less, I think that holds.

Working with LLMs on code feels like a similar inflection point. The skill isn't gone, it's shifting. You're not less of an engineer because you didn't hand-write every line. But you do still need to know what good looks like, arguably more than ever, because you're now the quality gate for a much higher volume of output.

What survives

In an era when anyone can produce reasonable-looking UI and code that compiles, the distinguishing markers become: taste, nuance, mature architectural opinions, and the contrarian calls that come from genuine expertise rather than pattern-matching.

It's noticeable to me that we are most successful guiding LLMs in the domains where we understand the code, the decisions, and the trade-offs most deeply. As we venture into the shallow ends of our skill sets, the outputs become markedly more impressionistic. Further from production-ready. More plausible-looking, less actually correct. The model doesn't know what it doesn't know, so it fills the gaps with confidence. Sound familiar? It's a very human failure mode, too.

But new skills are also emerging. I've started running what I call pre-mortems on complex plans: asking a fresh LLM session to assume the plan has catastrophically failed and diagnose why. It catches specification gaps that I miss after two days of being too deep in the details. One of our engineers built a tool that extracts rules from thousands of his past code review comments to seed an AGENTS.md file, essentially encoding years of implicit engineering judgment into instructions an LLM can follow. That's not the death of expertise. That's expertise being distilled.

The people who are finding their footing right now seem to share a few traits: they have strong opinions earned through practice, they can distinguish between principles that still apply and habits that were just bandwidth constraints, and they're willing to evolve their workflow without abandoning their standards.

A view from inside the loop

I don't think the current wave of AI represents the end of software engineering as a profession. I do think it represents a serious contraction and a fundamental reshaping of what the work is. The fear of obsolescence is legitimate. The fear of skill rot is legitimate. And the fear that if you don't go fast enough you'll be left behind is — while often overstated — not entirely unfounded.

But the bottleneck was never the code. It was always the human attention, the engineering judgment, the ability to hold a coherent vision for a system. We just didn't notice because writing code felt like the hard part. Now that it's being automated, those human capacities are revealed as the actual scarce resource. And scarce resources are valuable.

So if you're feeling overwhelmed, destabilized, simultaneously more productive and less happy, know that you're not alone. The team building the tools you're probably using to navigate this moment is feeling it too. We're debugging our reward functions in real time, same as you.

The code is changing. What we do with it is changing. How it feels is... a work in progress.

But the humans are still in the loop. We're just tired. And that's worth talking about.

We're building tools to make this less chaotic: Pydantic AI and Logfire. We're also hiring.